Translating a written text into another language requires a number of steps, and many more when it is for a minority language with a newly established orthography or alphabet and no or few previously written materials in that language. In the early days of transitioning translation projects from a purely manual process to a computer-assisted process, there were many pitfalls and challenges. But it was an exciting time for someone like me who loved a good challenge!

MS-DOS, (Microsoft Disk Operating System) was the dominant operating system for the personal computer (PC) throughout the 1980s. It was limited to a command line interface. This means that when you turned on a computer with this operating system, the only thing you saw displayed on the screen was “C: > _” in white letters on a black background. From there, you could type specific, cryptic text commands.

To say the least, it was quite scary for a person who was using a computer for the first time to see just this C: > (known as a C prompt) and a blinking cursor urging the user to type something. In the minds of many users, the cursor sent the message: “I need a command from you to do something! What are you waiting for?”

Working with a command-line interface was very intimidating, as if it were demanding the user to know exactly what command to type and the correct syntax or format it should be in. I quickly realized that it was imperative to develop some kind of interface to let the missionary or native user start the programs (today called applications or apps) they needed without having to memorize all the commands for each program, one by one.

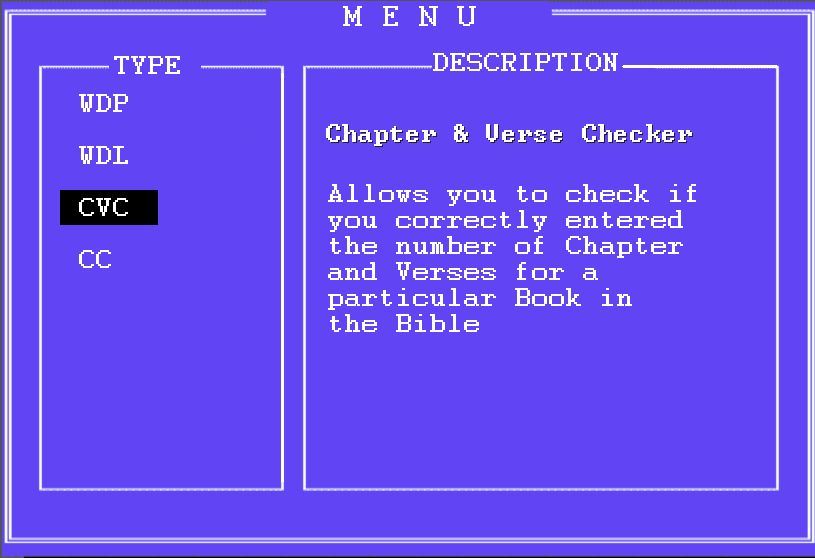

So I learned to use MS-DOS “batch” files (a file containing a list of commands which could be activated by typing the name of the batch file) and created a graphic interface, which appeared to the user as a menu. Each of the programs was represented by a two or three letter abbreviation with a short description next to it telling them what the program did.

Using the menu, a three-letter abbreviation such as WDP allowed them to start the word processor which was set up to open a split screen or window. In this way, they could have on one screen the original translation in Greek or Hebrew, or another major language like English, and on the second screen they would use the word processor to enter the translation into their target language.

WDL, another abbreviation, would start a word-list program that would provide them with a list of all the words in the text they had entered and how many times the word occurred. So when they had translated a chapter of a book of the Bible, they could run the Word-list program and print out a list of all the individual words in that chapter. This helped them to check the orthography and spelling of every word and then go back and correct their translation. Of course, they could also see the list on their screen but the monochrome LCD display was not easy to read and to make the transition from paper to display was an enormous step for all of us at that time. Most of the translators sat in front of their PCs with a Bible on their lap.

Another program provided a quick and easy way to find all occurrences of specified characters, words, or phrases in a text file or series of text files, and then change them consistently. The change could be done in every occurrence found or only when certain conditions were met.

This program called Consistent Changes (or CC) was like the find-and-replace feature in a text editor or word processor (like MS Word), but much more powerful. It allowed you to make changes, taking context into consideration, and also it could make a whole set of changes at once. This program worked beyond the search and replace feature. It had conditional logic controls and arithmetic and numerical controls that could be used to count items (characters, words, or phrases), insert or remove text, reorder parts of a file, and do many other things while processing the input file. (CC is without equal in the commercial world to this very day and you can still used it if you dare to learn it!)

In order to use the CC program, you needed to build a text file that described the changes you wanted to make. This file was called a “change table”. You could use an existing change table, modify an existing table, or create your own table.

Another issue that had to be considered was hyphenation. Some languages have very long words. This may require words to be hyphenated so a line of text in a paragraph could be broken in an appropriate place. Hyphenation rules are language dependent. The Hyphen program, another choice on my menu, would provide possible hyphenation points for all words over a certain length, using a coded list of hyphenation rules developed for that language. (In some cases, an existing hyphenation program within a word-processor could be used. To my surprise, I learned that one translator was using a utility for hyphenation in the German language to check and produce hyphenation in one of the varieties of Quechua languages spoken in Peru. It just happened to follow the same hyphenation rules as German!)

The number of these proprietary programs created to check the proper translation of the Bible was indeed numerous. Some were too complicated for the translator and required technical support to assist. Even after a translator was finished and thought his translation was “ready for publishing,” a team of technical specialists ran all the checks again and some others also. In most cases, the translator would have to travel, bringing their translation in diskettes, to United States or to another country where this checking and the final publishing of their translation would take place.

You must be logged in to post a comment.